Lübeck on the Brink of Disaster – 1946

Introduction

The diary of Sgt. Roy Tull (see: the experiences of Roy Tull) has been posted on the TracesOfWar website. This diary was made available to us by Barbara Tull, Roy's daughter.

At the end of 1946, Roy Tull returned to England, but the work of the RAF Bomb Disposal Squad

in Northern Germany was not finished.

That the work was not without danger is evident from a newspaper clipping Roy Tull kept in his diary, as well as from the investigative work of Ullrich Günther from Scharbeutz.

For an exhibition at the 'Museum für Regionalgeschichte in Pönitz' he and Karin Bühring, meticulously investigated everything that happened in the Lübeck Bay.

Partly through Roy Tull's story on the TracesOfWar website, he came into contact with Barbara Tull, who had photos and an article about an accident in the Lübeck Wallhafen on August 20, 1946.

Through his research, he also discovered the roles of Squadron Leader Hubert Dinwoodie from the County of Hampshire, Corporal Roland Norman Garred from the County of Sussex, and Leading Aircraft Man John William Hutton from Battersea, London.

The exhibition led to an interview with Barbara Tull by Sabina Jung of the Lübecker Nachrichten.

The newspaper Lübecker Nachrichten, through its editor Sabina Jung, Local Editor for Ostholstein, has given us permission to publish the interview on the TracesOfWar website, as can be read below.

The article from the 'Lübecker Nachrichten'

4/5 MAY 2025 - By Sabine Jung

Lübeck on the Brink of Disaster

In August 1946, an aerial bomb exploded during loading operations in Lübeck's Wallhafen harbor. A devastating chain reaction threatened to devastate large parts of the old town. Three British soldiers prevented this and likely saved thousands of lives. A story about forgotten heroes.

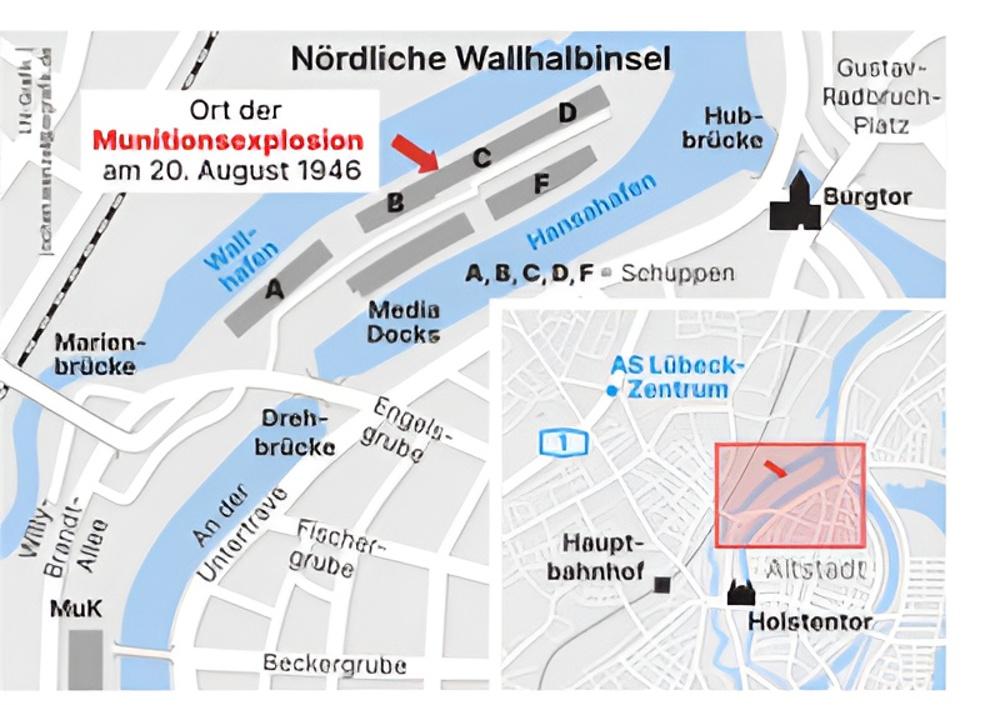

Lübeck.The aerial bomb hanging from a crane in Lübeck's Wallhafen harbor on August 20, 1946, was 1.10 meters long and weighed 54 kilograms. Suddenly, the explosive device slipped from the sling and crashed onto the pavement of the quay at the level of sheds B to D.

The explosion was powerful. Six workers died instantly, two later succumbed to their serious injuries. At least ten other people were injured. The accident was a catastrophe for those killed, for their families, and for the injured. And it threatened to become a catastrophe a thousand times worse – for Lübeck's old town and for the war-torn population living there. At this time, hundreds, perhaps thousands of tons more of ammunition were still stored at the Wallhafen harbor. A devastating chain reaction could turn the area within a radius of several kilometers into a hell of flames.

That didn't happen. The Wallhafen harbor still exists today, as does the entire northern Wall peninsula, the swing bridge and the lift bridge, the houses and streets along the Untertrave, and the Burgtor. Because three men showed courage and risked their own lives: Squadron Leader Hubert Dinwoodie from the County of Hampshire, Corporal Roland Norman Garred from the County of Sussex, and Leading Aircraft Man John William Hutton from Battersea, London. They belonged to a bomb disposal unit of the British occupiers. In Lübeck, their names remain largely unknown to this day.

Ullrich Günther from Scharbeutz, however, knows their names and their story. However, only recently, since his research for an exhibition at the Museum für Regional history in Pönitz.

It deals with "Ammunition in the Sea – The Explosive Legacy," with 1.6 million tons of dumped ordnance in the German parts of the Baltic and North Seas, the risks of these legacy wastes, and the pilot project for their recovery. "

"I tried to find out everything about the dumping in the Bay of Lübeck," reports the museum employee."

One discovery led him to the next. On the website "Traces of War," Ullrich Günther came across Sergeant Roy Tull, a member of the Royal Air Force (RAF) Bomb Disposal Squad after World War II, stationed in Lübeck.

This Roy Tull kept meticulous records of the munitions dumped in the Baltic Sea and all the related events in 1945 and 1946. He left his daughter Barbara Tull a wealth of notes and photos from that time – including recordings and images of the explosion at Wallhafen and the deployment of Dinwoodie, Garred, and Hatton on August 20, 1946.

Using these documents, as well as publications

on British websites and old newspaper articles,

Ullrich Günther has reconstructed the events of

that day. At the time, Lübeck was one of the

loading ports for the munitions that were to be

dumped in designated zones in the Bay of

Lübeck. From arsenals and munitions factories

in Schleswig-Holstein and Lower Saxony, trains

and trucks packed with the dangerous cargo

rolled into the Hanseatic city, where grenades,

bombs, mines, torpedoes, and cartridges were

loaded onto ships.

When the aerial bomb exploded at the Wallhafen harbor, eleven other bombs of this type- "SC 50" or "SD 50" -were lying on the quay. Additional ammunition is stored in two nearby freight trains,which, according to a munitions expert's calculations, together contain more than 30 tons of pure explosives. Due to the risk of explosion, the port authority closes off the area and requests assistance from the British occupation forces.

Hubert Dinwoodie, a squadron leader in the RAF bomb disposal unit, is al the time in Lüneburg Heath, at the Starkshorn naval interdiction arsenal. He volunteers for deployment in Lübeck. The explosives expert,then 50 years old, brings Corporal Roland Norman Garred (23) and the driver William Hatton (24) to the Wallhafen harbor. They are to defuse the eleven aerial bombs stored on the quay. Apparently, however, its design is unknown. "It is a new design with faulty workmanship," explains Ullrich Günther. The slightest shock could lead to detonation. Dinwoodie determines that it is a special ignition safety device and that the ignition mechanism has slipped.

He later described the situation to a British newspaper as follows: "The fuse was (...) about the size of a lady's wristwatch, and we weren't sure exactly where it was located in the casing. It only took a movement of one-eighth of an inch in the wrong direction to detonate it."

One-eighth of an inch is about three millimeters. Dinwoodie, Garred, and Hatton carried the eleven bombs across the quay, loaded them onto a boat, and sailed down the Trave River to a remote detonation site, where they detonated the explosives. "Unfortunately, we never found out exactly where this site was," said Ullrich Günther regretfully. Dinwoodie and Garred then examined the ammunition in the trains parked at the Wallhafen harbor. Hatton used his truck to tow away a wagon damaged by the explosion to separate it from the rest of the train. Dinwoodie ultimately decided: The remaining ammunition can be dumped in the Baltic Sea. The entire defusing operation at Wallhafen took four days.

This depiction sounds realistic, explains Uwe Wichert, a retired naval officer in the mine countermeasures division and member of the "Munitions in the Sea" expert group of 'Expertenkreis „Munition im Meer“ des Bund-Länder-Ausschusses Nord- und Ostsee.' He has subjected the old images from Wallhafen to a forensic analysis. The damage pattern suggests that the detonated aerial bomb carried either 16 kilos or "only" 5.5 kilos of explosives. Uwe Wichert estimates that each of the wagons shown in the photos could have contained up to 106 bombs. He has calculated that the two trains, each with six wagons, could have contained a total of almost 32 tons of pure explosives.

“It is a tragic accident in which people lost their lives and British soldiers risked their lives to prevent further and greater damage,” reads Ammunitions expert Wichert's conclusion about the explosion on August 20, 1946. "My highest respect goes to these men."

In 1947, Hubert Dinwoodie received who, in his homeland, was awarded the George Cross, the highest civilian decoration for gallantry, for his actions. British soldiers receive it when this gallantry was not performed in the face of the enemy. "Throughout the operation, Squadron Leader Dinwoodie displayed cold-blooded heroism and initiative under extremely critical circumstances," reads the website of the Victoria Cross and George Cross Association. Roland Norman Garred is being honored with the British George Medal for demonstrating "courage and devotion to duty of the highest order." John William Hatton is receiving the British Empire Medal for his "efficient and diligent work, fully aware that he was standing directly next to ammunition-laden trains and eleven shock-sensitive bombs."

Barbara Tull discovered parts of this story in the notes and photographs of her father, who died in 2003. "My father didn't talk much about the war himself," she reports. "Nobody did back then." She is in contact with a grandson of Hubert Dinwoodie, and she has an acquaintance who works in the archives of the RAF Museum in London and who helped fill in some of the gaps.

"They were heroes," says Barbara Tull about Dinwoodie, Garred, and Hatton. "They wanted to protect lives, and it would be nice if people in Lübeck knew about their efforts." Ullrich Günther inquired with the Lübeck City Archives. "But they only knew about the explosion. The background is apparently unknown," he says. "Unfortunately, despite intensive research in the database and the storage rooms of the city archives, no references to any records of the event could be found," confirms Nicole Dorel, spokesperson for the Lübecker City Archives.

The fact that no records of the event exist could be explained by the fact that responsibility lay with the British military authorities or even state authorities, "so that the relevant documents are now in the state archives in Schleswig or in British archives."

Barbara Tull would be pleased to see a memorial to the three men, perhaps in the form of a plaque on one of the sheds at the Wallhafen. This would also be in the spirit of Hubert Dinwoodie's grandson, who himself does not want to appear in public, she explains. This idea has been met with open ears by Jörg Sellerbeck, spokesperson for the 'Projektgruppe Initiative Hafenschuppen' (PIH) project group. The PIH development and development company is implementing the long-discussed conversion and development of the northern Wall peninsula. The city of Lübeck has sold sheds A to D and F, as well as two new construction areas, to the project participants.

"It's not only conceivable, but desirable, that the incident be commemorated, for example, by means of a plaque," says Jörg Sellerbeck. "The same has already been suggested regarding the participation of prisoners of war in the construction of Shed F between 1939 and 1945."

Barbara Tull now knows what Lübeck's Wallhafen looks like today. She traveled from her home in Somerset to Pönitz for the opening of the exhibition on April 13 of this year. After her arrival, her first stop was the northern Wall peninsula. The crane that can be seen in her father's photos is no longer there. But the remaining historic cranes resemble it, the British woman believes, and that it was good to visit this place: "It was a truly emotional moment there in the harbor."

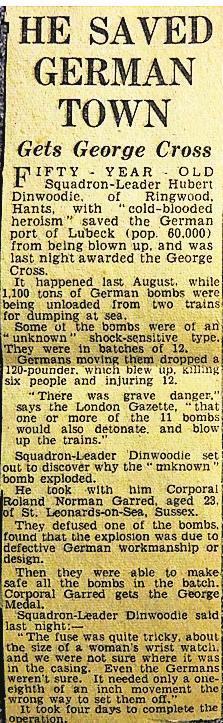

"He saved a German city"

A newspaper clipping reporting on the operation in Lübeck was found in Roy Tull's estate. The translation in excerpts:

"Fifty-year-old Squadron Leader Hubert Dinwoodie of Ringwood, Hants, saved the German port of Lübeck (population approx. 60,000) from an explosion with 'cold-blooded heroism' and was awarded the George Cross last night.

It happened last August when 1,100 tons of German bombs were unloaded from two trains to be dumped at sea. Some of the bombs were of an unknown, shock-sensitive type. (...) German workers dropped a 120-pound bomb, which exploded, killing six people and injuring 12 others.

'There was a grave danger,' reported the London Gazette, 'that one or more of the remaining 11 bombs might also detonate and blow up the trains.'

Then they were able to make

safe all the bombs in the batch

Corporal Garred gets the George Medal.

Squidron-Leader Dinwoode sald

last, night:“The fuse was quite tricky, about the size of a Woman's Wrist watch

and we were not sure where it was

in the casing. Even the Germans

werent sure.” It needed only one eighth of an inch movement the wrong way to set them off."

It took four days to complete this operation.