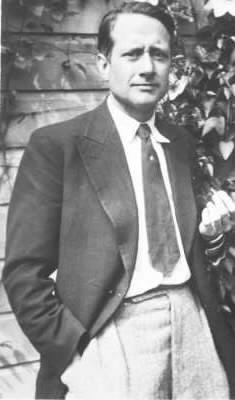

Gerrit Jan van der Veen

Introduction

‘What do you do, now that your country is kicked and enslaved,

Now that it bleeds from countless wounds.

What do you do, now that your people are being emasculated and disenfranchised,

By the black and field-grey dogs?’

These lines of poetry are by the well-known resistance fighter Gerrit Jan van der Veen and are taken from an article he wrote for the illegal magazine The Free Artist (De Vrije Kunstenaar).

Who was this man? What did he contribute to the effords of the Dutch resistance? How did he grow to become one of the best known of the Dutch resistance fighters?. This article endeavours to answer these questions.

Before the War

Youth

Gerrit Jan was born in Amsterdam on 26 November 1902, the third child of the butcher Gerrit Jan van der Veen and his wife Dorothea Lorenz. He had two older brothers and a younger sister. Their butcher's shop was located in the Jordaan district. He came from a Reformed family.

Immediately after his birth he contracted a severe case of pneumonia, which he barely survived. Gerrit Jan van der Veen remained a rather sickly child. He suffered from measles and had to stay home from school.

Despite his fragile health, he successfully completed preparatory school on Da Costastraat. He then went to the three-year HBS (High School), also in Amsterdam. After graduating, it took him some time to decide what to study next. He considered becoming an artist, but the uncertain prospects in that field led him to go another direction.

Career with the railways

Like his older brother Gerrit Jan, next studied mechanical engineering at the railway school in Utrecht. After completing the six-year course in 1923, he began his professional life in the drawing office of the railway company, also in Utrecht. However, he remained active as an artist. He drew a lot and also carved wooden figures. One of these figures won a prize at a sculpture exhibition in Zaandam in (1924).

In his spare time, he created comics with his brother. He and his brother rented an old shop to work in. Gerrit drew the pictures and also built a projector. These comics were used for advertising. Sometimes the brothers were successful, but often they could not pay the rent for the shop.

For a total of three years, Gerrit Jan van der Veen worked in the drawing department, but it gave him little satisfaction. He found the work too monotonous. Moreover, his prospects were not good, partly because the railways had to make cutbacks.

In service of the Bataafse Petroleummaatschappij (Batavian Oil Company)

So Gerrit Jan was delighted when the Bataafse Petroleummaatschappij (BPM) offered him a job as a mechanic at their refinery in Curaçao. When he was 24, he went to this Dutch colony, which was heavily dependent on the oil-processing industry there, In those days, at the end of the 1920s, safety regulations for such installations were still inadequate. Explosions occurred regularly, resulting in injuries and sometimes deaths. Gerrit van der Veen often volunteered to help in extinguishing the fires and the search for victims.

One day a fire broke out in the engine room of a British tanker docked in the port of Curaçao. The British crew fled the ship for fear of an explosion, allowing the fire to spread. Volunteers were called in to put out the fire. The story goes, that Gerrit didn't hesitate to jump into the water. He swam to the ship and used the fire extinguishers on board to put out the fire. This earned him hero status for saving the harbour from disaster.

Gerrit Jan was rewarded for his efforts. The board of Directors spoke of rare opportunities for promotion and even the creation of new and very lucrative roles for him. But he didn't respond. He decided to fulfil a long-held dream and asked them to finance his training as a sculptor at the Academy of Fine Arts. The board was rather surprised, but eventually agreed. The reward turned out to be rather small. He received a one time payment of just 500 guilders and a monthly allowance of 60 guilders for a year for living expenses. The BPM had saved millions and had escaped disaster. But Van der Veen had to accept this relatively small sum. He left Curaçao and arrived in Amsterdam at the end of 1928.

Training and work as a sculptor

In Amsterdam he began his training at the State Academy of Fine Arts. He was to specialize in sculpture. The first few months were not easy. He was clearly talented, but the other students regarded him as an outsider because he had less experience and because he had worked in another field before entering the academy. This did not discourage him. He worked hard and got better and better. It was during this time that Gerrit Jan met his future wife, Louise Adriana van der Chijs (1909-1997).

Gerrit Jan then studied at the National Academy of Fine Arts. For a while he worked for an advertising agency. In 1931 he decided to devote himself entirely to sculpture. On November 25 of that same year, he married Louise van der Chijs. They had two children, Louise (1933-2020) and Gerda (1935-2006).

The early years as a sculptor were not easy for Van der Veen and his family. There were financial problems and they often had to borrow money to pay for gas and electricity. Later things were better. His first major commission was a clock for a square in Willemstad, Curaçao. He also made sculptures of well-known artists and professors. He was even allowed to work for the royal family (he sculpted a Portrait of Princess Juliana in bronze).

In addition to sculpture, Van der Veen was also involved in the production of tokens for weddings and the like. He was commissioned by the Bank of The Netherlands to create new designs, and spent many days at the Enschede company in Haarlem, where these banknotes were printed. This gave him a great deal of knowledge about the printing process. He was also familiar with the watermark and how it could be forged. This knowledge would come handy later.

Unarmed resistance

German invasion and beginning of resistance work

On May 10, 1940, the Netherlands was invaded by Nazi Germany. This shocked Van der Veen. Before the invasion, he had shown little interest in politics. This changed after the surrender of the Dutch army. Although the first months of the occupation were relatively quiet, Van der Veen looked for ways to resist.

He was head of the local branch of the Air Defence Service. In July 1940, all members of this service, like all other Dutch civil servants, were asked to sign a declaration stating whether they were Jewish or Aryan. Van der Veen categorically refused to sign the so-called Aryan declaration. This was his first act of resistance.

On November 25, 1941, the Reich commissioner for the occupied Netherlands (Arthur Seyss-Inquart) established the ‘Kultuurkamer’ [Cultural Chamber]. Anyone involved in any form of art had to report to this institution. Anyone who refused to comply risked a heavy fine. The Dutch ‘Kultuurkamer’, was headed by Tobie Goedewaagen, a member of the NSB: (Nationaal Socialistische Beweging, Dutch Nazi party). He was charged with ensuring that all cultural expressions were dedicated to Nazi ideology. Their motto’s were: nationalist attitude, attachment to country and people, historical consciousness, elimination of all degenerate, unhealthy, unnatural creativity, a positive Germanic attitude.

From the outset, Gerrit Jan was a fierce opponent of the Kultuurkamer, which was created by the occupying forces, and severely restricted the personal and inner freedom of artists. At a meeting of the Dutch Sculptors' Circle, of which he was secretary, he insisted that no one should report to the Kultuurkamer. When not everyone agreed, he left the meeting with the treasurer, Leo Braat (who also took the Circle's cash box with him), and two allies. The money was to be used to support artists who refused to become members of the Kultuurkamer and who, as a result, could no longer work.

Together with several others, Van der Veen also wrote a manifesto to the Reichskommissar, which was published in February 1942. The manifesto, in which they argued that they should be free to express their art and that they would not accept any political interference, was signed by over 1900 people. After some of the authors of the manifesto were arrested, Gerrit Jan decided to go into hiding. His family was later forced to do the same.

On May 1, 1942, Gerrit Jan founded the underground magazine ‘De Vrije Kunstenaar’ (The Free Artist). He was the editor, but he also did couriers work and even helped with the layout. Thousands of copies were printed. The magazine had a fairly wide circulation. Among other things, it contained the ‘Brandaris brieven’‘ (Brandaris letters), which called for resistance. These letters were written by, among others, Willem Arondeus (1894-1943), a visual artist who would be involved in the attack on the Amsterdam Bevolkingsregister (Population registry). Van der Veen also wrote a pamphlet protesting against the deportation of the Jews, which he compared to a modern form of slavery.

Identity Card Centre

Gerrit Jan however, wanted to go further than mere verbal resistance. In their persecution of Jews and others, the Germans benefited greatly from the excellent population records kept in the Netherlands. From April 1941, every Dutch person over the age of 14 had to carry a personal identity card. This made it very easy for the occupying forces to arrest wanted persons. Jews were easy to track down because they had a large J stamped on their identity card.

After the introduction of the identity card, the Dutch resistance immediately set about falsifying them. This project, which they called the Persoonsbewijzencentrale (PBC) or Identity Card Centre, proved to be a major challenge. Particularly difficult to copy were the watermark, the changing of the passport photo and the ink used. The first person to produce a usable forgery was the illustrator and playwright from The Hague, Eduard Veterman (1901-1946). His forgeries were of high quality. But Veterman could not produce them in large quantities.

Gerrit Jan was looking for a high quality design that could be printed in large quantities. His experience in printing banknotes was very valuable.

However, it took several months before Gerrit Jan was able to produce a satisfactory imitation of the identity card. The watermark was a problem, and it was not until Christmas 1942 that he found a solution that provided a satisfactory forgery.

The false identity cards were printed in the printing works of Frans Duwaer (1911-1944). This was no easy task, as it was very difficult to obtain the right type of paper. It was also necessary to use a special typeface that was not freely available. A mechanic at the printing office where the identity cards were printed, who was sympathetic to the Resistance, helped to obtain this typeface. Eventually, at its peak, Duwaer’s printing works printed 800 identity cards a week. The printing had to take place on Sundays so that the other employees of Duwaer remained unaware of the illegal activity.

In addition to identity cards, the Identity Card Centre was also involved in the forgery of ration cards, food stamps and all kinds of Ausweise (permits from the Germans to do one thing or another). Eventually, the facility would employ about a hundred people. More than 65.000 identity cards and 75.000 food stamps would be forged.

Armed resistance

However, the excellent Dutch population records remained very convenient for the Germans. They could easily determine whether an ID was fake or not through a simple check. They used these records to call up people for forced labour in Germany (the Arbeitseinsatz). Together with other people, Gerrit van der Veen made several attempts to sabotage (parts of) this administration.

The first attack was directed against the map room of the Amsterdam Labour Office and took place on February 10, 1943. It was carried out by Van der Veen and two other resistance fighters. If they succeeded in destroying the map room, it would be difficult for the Germans to determine who should be called up for labour service. The plan was to call the porter at the labour office and tell him that the director and two Germans were coming to the office to discuss some matters. When they entered, the staff present would be overpowered and the fire set.

The plan succeeded up to a point. Van der Veen and his allies managed to enter the labour office. They overpowered the doorman and tied him up. Then they went to the map room and started the fire. But the porter managed to escape and raised the alarm. As a result, the fire was quickly discovered and extinguished. Damage to the administration building was limited.

Raid on the Populations Registry

On March 27, 1943, Gerrit Jan van der Veen and several other members of the resistance raided the Amsterdam Population Registry at 36-38 Plantage Kerklaan. This building contained the details of over 700,000 Amsterdam citizens, including 70,000 Jews. If these records could be destroyed, the Germans would lose an important tool and means of detection.

The raid went according to plan. Nine resistance fighters, six of them wearing police uniforms, entered the Population Registry of Amsterdam under the pretext of carrying out a check. Willem Arondeus, who was in charge of the operation, ordered all the guards to come forward. They were then disarmed and temporarily incapacitated by a narcotic injection.

The group then began to open the filing cabinets and empty the card boxes. A flammable liquid was sprinkled over the piles of documents and explosive charges were placed. At around 11:00 a.m., a series of heavy explosions was heard and the building was engulfed in flames. The fire brigade took longer to arrive and used far more water than was strictly necessary, all in an attempt to make the damage as great as possible.

In the end, it turned out that only 15% of the records had been destroyed. Moreover, the occupying forces had a duplicate of all Dutch personal data in the Kleykamp villa in The Hague. (This villa was to be bombed by the British Air Force in 1944.) So the operation did not have the desired effect. What's more, most of the attackers were arrested soon afterwards. Only Gerrit Jan van der Veen and the graphic designer Willem Sandberg (1897-1984) managed to escape the Germans.

Central man of resistance

More and more, Gerrit Jan van der Veen became the key figure in the Amsterdam resistance theatre. Through an illegal radio channel, he came into contact with the Dutch government in exile in London, which soon regarded him as the key figure in the Dutch underground. Due to his disguise, he was known there by the nickname "the bowler hat".

At the end of 1943, Van der Veen, together with Gerben Wagenaar and Paul Guermonprez, took over the leadership of the Resistance Council (Raad van verzet, RVV), an underground group that was mainly involved in armed resistance and sabotage. The RVV also sought to unite and coordinate the Dutch underground. When Gerrit Jan realised that the RVV did not have unanimous support (for example, in addition to the RVV, the Landelijke Knokploegen, (National Resistance) and the Ordedienst (Order Service) were also involved in armed resistance), he withdrew from the leadership. His main concern was the Identity Card Centre (Persoonsbewijzencentrale PCB).

Van der Veen stayed with Kern (core), a regular summit of the main resistance organisations in the Netherlands. At these meetings they coordinated their activities and tried to come closer together.

Armed robbery

Raid on the National Printing Office at The Hague

The Personal Identity Card Centre (PBC) managed to produce reasonable fakes. They could pass initial tests, but failed when subjected to more extensive scrutiny. Moreover, counterfeiting was a difficult and lengthy process.

An employee of the PBC, Frits Reinder Bovenhuis, suggested a raid on the Federal Printing Office in The Hague. This was the place where all Dutch identity cards were printed and where thousands of blank copies were stored. It would be a great relief to the PBC if Gerrit Jan succeeded in capturing these documents.

The raid took place on April 29, 1944. Van der Veen and four allies (German-Jewish immigrant Gerhard Badrian in SS uniform, Amsterdam detective Cornelis Verbiest and PBC employees Hans van Gogh and Franciscus Meijer) entered the printing office on the pretext of an inspection. Badrian ordered the manager to open the safe. The few employees present were quickly overpowered. The robbery was a success. The group made off with 10,000 documents and was able to return to Amsterdam without problems. However, some of the stolen documents later fell into the hands of the Germans.

Raid at the House of Detention on the Weteringschans

The Detention House at Weteringschans prison in Amsterdam was a notorious place during the war. Many resistance fighters arrested by the Sicherheitsdienst (SD, Security Service) were held here before being executed or interned in a concentration camp. Van der Veen had made several plans for a raid on the Detention House to free the prisoners.

His first idea dates back to September 1943. One of his aims was to free his fellow resistance fighter Walter Brandligt. When Brandligt was executed in the dunes of Overveen in October 1943, Gerrit Jan abandoned the idea of a raid for the time being.

Gerrit Jan made another plan for a raid on Christmas Eve 1943. The plan was to drive a truck to the detention centre and enter the building on the pretext of carrying out an inspection. Badrian would pose as a German officer. They would overpower the guards and free a number of prisoners. However, this plan could not be carried out because Gerrit Jan was unable to find a suitable vehicle for the raid. On New Year's Eve, he and his group wanted to make a new attempt but no suitable truck had yet been found and the raid had to be postponed again. On January 7, 1944, the raiding party made a third attempt. It went wrong again. This time they managed to find a truck, but just as it was being driven out of the garage, it was attacked by the Sicherheitspolizei. A shoot-out ensued and Gerrit Jan and one of his employees narrowly escaped. However, a number of Gerrit Jan's allies were arrested.

Gerrit Jan was not easily discouraged. More and more of his friends and comrades were arrested. He was determined to free them despite his co-workers who strongly advised him to give up and even the Dutch government in London, which tried to persuade him of the need to remain available for leadership roles during and after the war. Loe de Jong, (author of the multi-volume work 'The Kingdom of the Netherlands in the Second World War') wrote about Gerrit Jan: 'In the tremendous stress under which he lived as the man who led the widespread underground movement, he obviously needed the relief that came with action.

Gerrit Jan planned a new raid for Monday the first of May 1, 1944. He had 28 armed resistance fighters with him, and he was also in contact with the prisoners and with a prison guard sympathetic to the resistance, who helped prepare the raid. This guard also provided a map of the prison. It was agreed that the trusted guard would open the door. The resistance fighters would overpower the other guards. The prisoners would be freed.

The resistance fighters went to the Weteringsschans in small groups of four. They were let in by the trusted guard who opened the door. On entering, Van der Veen was attacked by a guard dog which he shot. The resistance group had already been informed that dogs would be present. If they were caught, the whole prison would be alerted. But this was not reason enough for Gerrit Jan to postpone the attack.Van der Veen refused to postpone the attack.

Gerrit Jan’s shots alarmed the German guards. A firefight ensued between them and the resistance fighters, who were forced to break off the attack and to withdraw. Gerrit Jan was hit in the back by two bullets, presumably fired by one of the resistance people. This caused a paralysis in both his legs and he was no longer able to walk. He was carried away from the Weteringsschans by four of his comrades.

He was taken to the De Spiegel (the Mirror) publishing house at the Prinsengracht 856, where Susan van Hall was employed. She was the niece of Walraven van Hall, the head of the Nationaal Steunfonds (National Welfare Fund). She was also an employee of the Personal Identity Centre and she had a love affair with Gerrit Jan. Even before the prison raid, Gerrit Jan used the publishing house as a hideout. He decided to stay there and seek medical treatment. He was examined by a doctor who managed to remove one of the bullets. The other bullet was near his coccyx and could only be removed by a specialist surgeon. It was difficult to find such a person. Moreover, there was a risk that the operation would make his situation worse.

For many days Van der Veen lay in the Prinsengracht premises. His lower body was paralysed and he was incontinent. Four women looked after him. He was offered another hiding place, but he refused. He wanted to remain in a familiar place. This was despite the fact that the hiding place at De Spiegel was known to many underground workers.

Arrest and death

On May 12, 1944, SD (Sicherheitsdienst) men entered the De Spiegel building. Their knowledge of the address was assumed to be a betrayal, but it was never clarified. Gerrit Jan van der Veen tried to avoid arrest by escaping over the roof. But in his semi-paralysed state, this was doomed to fail. Together with his girlfriend Susan van Hall and two others, he was arrested and taken to the Weteringsschans. He was transferred several times to other prisons, presumably to prevent attempts by the Dutch underground to free him.

The first days, Van der Veen managed to keep silent despite German pressure. Later he confessed to the Germans things that they already knew.

Trial and execution

A mock trial was held on June 10, 1944, an SS and police court sentenced Gerrit Jan to death together with several others, including Frans Duwair and Paul Guermonprez (both of whom had worked with Van der Veen, including in the RVV). The sentence was carried out the same day.

Before their execution, the prisoners were each given the opportunity to write a farewell letter. In his letter to his wife, Van der Veen wrote openly about his extramarital affairs. Besides Susan van Hall, he had an affair with Gustave (Guusje) Rubsaam, with whom he fathered a son, who was born on August 9, 1944 and was named after his father. This son became the future politician Gerrit-Jan Wolffensperger (in the liberal party called D66).

"In the end, everything went wrong. It is unfortunate, but with all the millions who have fallen and the many who yet will fall, my person sinks into insignificance. I always knew what I was risking and I have no complaints. But it remains unfortunate. I wanted to do what was my duty. I couldn't have done otherwise.

On the evening of June 10, 1944, Gerrit Jan van der Veen, physically supported by two comrades, was shot dead by a German firing squad together with seven others in the dunes of Overveen.

Conclusion

After Van der Veen's arrest in May, Gerhard Badrian took over the management of the Persoonsbewijzencentrale (PBC). But as a result of treachery Badrian was killed 20 days later on June 30, 1944 in a shoot-out with an SD-Sonderkommando. The Persoonsbewijzencentrale was then decentralised. According to Loe de Jong (author of the multi-volume work “The Kingdom of the Netherlands in WWII), it was run by a number of Amsterdam students, including Samuel Albert (Boet) de Lange. Other sources mention as a possible leader of the PCB Wienik Everts (1912-1990), born in Makassar, who was known during the war under the pseudonyms Klaas van Veen, Tom or Nico van der Poll. According to some, Walraven van Hall was also involved. After Van der Veen's death, the organisation was in danger of falling apart. Van Hall, who was a great mediator, managed to prevent this.

After the liberation Van der Veen was buried in the honorary cemetery in Overveen.

A street in Amsterdam is named after him. During the German occupation, various German institutions were located in the Euterpestraat in Amsterdam. These included the Sicherheitsdienst (SD) and the Zentralstelle für Jüdische Auswanderung (which dealt with the deportation of Dutch Jews). Many resistance fighters, before being sent to a concentration camp, were first interrogated and tortured by the SD which had its headquarters on this street. This made the Euterpestraat a symbol of German repression in the Netherlands. After the war it became clear, that this name could not be held. Too many bad memories. The street had to be renamed. It was named after one of the most famous freedom fighters, Gerrit Jan der Veenstraat.

Gerrit Jan gained much fame for his armed actions.His attacks and raids were not always successful, but he sent a clear message, that not everyone would simply accept the German occupation. His most important contribution to the resistance was his leadership of the Persoonsbewijzencentrale. This organisation saved thousands of people from deportation to concentration camps and forced labour in Germany. This gave Gerrit Jan van der Veen a heroic status during and especially after the war. For example, he was the first resistance fighter to have a biography written, 'Een doodgewone held' (An Ordinary Hero), by Albert Helman, first published in 1946). His story has also been the inspiration for a number of Dutch films. The character of Peter van Dijk (played by Jeroen Krabbé) in the film 'Riphagen', about the Amsterdam criminal Dries Riphagen, is based on Gerrit Jan van der Veen, played by Peter Blok. Gerrit Jan is also one of the protagonists in the exhibition 'The Netherlands in the Second World War' at the Overloon War Museum. This fame is justified for a man whose contribution to the Dutch resistance was enormous.